Placental abruption not caused by trauma is typically a result of blood clotting in the maternal blood pool located behind the placenta. This clotting is usually due to inadequate blood volume, which is often a consequence of insufficient nutrition.

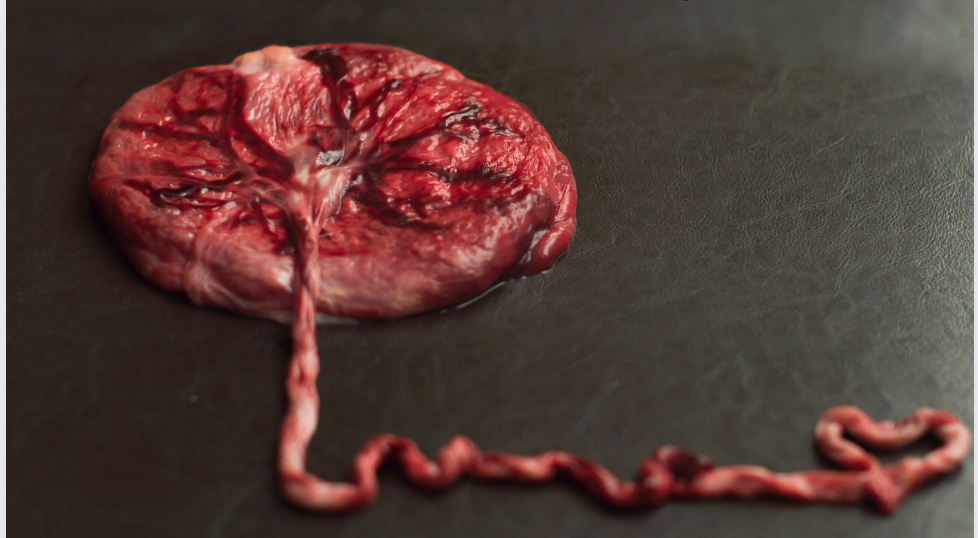

When the placenta attaches to the inner uterine wall, it secretes enzymes that dissolve the ends of the capillaries coming to the surface of the uterus. This process forms an arterial-venous shunt where blood is exchanged between the mother and baby. A pool of blood forms behind the placenta, and the baby’s capillaries in the placenta continuously receive nutrients and oxygen from the mother’s blood while discarding waste products.

Throughout pregnancy, the mother’s blood volume and the blood pool behind the placenta must increase to meet the growing demands. For a singleton pregnancy, the mother needs to increase her blood volume by 60% (about 2 litres of blood), while for a twin pregnancy, this requirement rises to 100% (about 3.5 litres of blood). To achieve this, the mother must consume a minimum of 2600 calories, add salt to her diet as desired, and consume 80-100 grams of protein for a singleton pregnancy (more for a multiple pregnancy).

If the mother fails to meet her body’s increased blood volume requirements due to inadequate food intake, fluid and salt loss (from overheating or herbal diuretics), or a lifestyle that burns extra calories, the blood flow through the arterial-venous shunt behind the placenta slows down. This reduced flow leads to clotting in the blood pool behind the placenta.

To prevent this clotting, it is essential for the mother to follow the recommendations of the Brewer Pregnancy Diet. Additionally, she should make personalised adaptations to meet her unique lifestyle and needs, ensuring her body can maintain an adequate and expanded blood volume throughout the pregnancy. This will help maintain a healthy flow of blood through the capillaries behind the placenta and prevent clotting.

There are two essential points that require emphasis:

The human placenta creates an ARTERIO-VENOUS SHUNT (A/V) in the maternal circulation. During the last trimester of a normal pregnancy, approximately 50 to 60 jets of arterial maternal blood surge against the fetal cotyledons with each maternal cardiac systole. This blood circulates in the intervillous space and returns to the uterine venous system through “tub drains.”

The A/V shunt necessitates an INCREASING MATERNAL BLOOD VOLUME throughout the second trimester, reaching a plateau that must be maintained throughout the entire third trimester, to ensure optimal fetal growth and development.

The failure to recognise these well-established facts has had significant repercussions on human maternal-fetal health in the western world, particularly in the USA, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Reduced utero-placental blood flow associated with common human reproductive pathology has not been correctly attributed to hypovolemia and the failure to maintain a physiologically expanded maternal blood volume.

Physicians often impose dietary restrictions on calories and sodium and prescribe drugs, diuretics, sodium substitutes, vasodilators, etc., which, in fact, cause or exacerbate maternal hypovolemia. Intrauterine fetal growth retardation (IUGR) and small for gestational age (SGA) babies have seen a dramatic increase since the 1950s, particularly in these three nations, where medical authorities universally deny the role of prenatal malnutrition in causing human reproductive complications. Incorporating applied physiology and basic nutrition science into human prenatal care as a routine for all women throughout gestation should form the foundation of true primary prevention in this field.

Abruption of the placenta, where it separates prematurely from the uterine wall before the baby is born, is one of the most dangerous complications in obstetrics. Traumatic abruption occurs due to accidental abdominal puncture wounds suffered by the mother, an unfortunate occurrence independent of nourishment. However, in most cases, abruption is a severe consequence of malnutrition. It is more commonly observed among economically disadvantaged individuals, with medical literature reporting numerous instances of recurrent abruptions in the same mother. Abruption often coexists with underlying metabolic diseases, such as MTLP.

Any degree of abruption poses an immediate threat to the baby’s survival, as oxygen transfer to the baby ceases once the placenta detaches. Toxic waste quickly accumulates in the baby’s tissues, and the brain can only survive eight minutes of oxygen deprivation before irreversible damage occurs. Roughly 50 percent of babies die before mothers with this complication can reach the hospital. Immediate delivery becomes the only treatment option. An effort is made to save the baby if possible, while simultaneously minimising internal blood loss and the resulting shock that can also endanger the mother.

Nontraumatic abruptions do not tend to occur in well-nourished women. Adequate nutrition before pregnancy and during early pregnancy promotes secure implantation of the placenta on the uterine wall, and continuous good nutrition ensures that the placenta grows to meet the developing baby’s demands.

Other potential causes of placental abruption

A lack of oxygen to the placenta and the developing baby can be caused by various conditions that lead to poor oxygen flow. One such condition is sleep apnea, a sleep disorder characterised by brief interruptions in breathing during sleep. Sleep apnea can lead to reduced oxygen levels in the mother’s bloodstream, affecting the oxygen supply to the placenta and, consequently, to the baby.

Other conditions that may result in poor oxygen flow to the placenta and the baby include:

Hypertension (high blood pressure): Chronic hypertension or gestational hypertension can reduce blood flow to the placenta, affecting oxygen delivery to the baby.

Preeclampsia: A severe condition characterised by high blood pressure and damage to other organs, preeclampsia can disrupt blood flow to the placenta, leading to oxygen deprivation.

Smoking: Smoking during pregnancy can constrict blood vessels and decrease blood flow to the placenta, causing oxygen deprivation for the baby.

Drug or alcohol use: Substance abuse during pregnancy can harm blood vessels and impede the flow of oxygen to the baby.

Anemia: Insufficient red blood cells in the mother’s bloodstream can decrease oxygen-carrying capacity, affecting the baby’s oxygen supply.

Placenta previa: In this condition, the placenta partially or fully covers the cervix, potentially leading to compromised blood flow and oxygen delivery.

Uterine abnormalities: Certain abnormalities in the uterus can interfere with proper placental attachment and blood flow, impacting oxygen supply to the baby.

Maternal heart or lung conditions: Certain cardiac or pulmonary issues in the mother can reduce oxygen levels in the blood and affect placental function.

For more information relating to placental abruption please click here